Playing with Water

Image courtesy of the One Art Museum, Beijing

Chinese to English is one of the language pairs I translate, and texts of an artistic nature are among my thematic focus areas. As such, apart from the work I do for my regular clients, I’m always on the lookout for Chinese articles, press releases, exposés, and opinion pieces that I can translate into English and share with a wider audience.

The classical elements of fire, earth, air, and water that we are familiar with and that come to us from Ancient Greece are not the same as those used in Ancient China. Instead, in Ancient Chinese cosmology and philosophy, the elements are earth, wood, metal, fire, and water.

In the Chinese cultural space, each year is associated with an animal from the Chinese zodiac, but what’s less well known is that each year also has an element attached to it. The article I’ve translated below, on the breathtaking sculptures of Beijing-based artist Zheng Lu 郑路, was originally published in 2023—fittingly, in the year of the Water Rabbit. In combination, the element and the sign are said to represent flexibility, malleability, and the action-inaction dichotomy (flowing water versus still water), while the Rabbit is associated with traits such as elegance, beauty, and thoughtfulness.

The original Chinese article can be found here.

One Art Exclusive | Zheng Lu: Through art form integration to poetic elegance

The One Art Museum’s public art exhibition Field Towards the Future, sponsored by Beijing-based developer Strong Park, is officially showing from 8 November 2022 until 20 May 2023. Cheng Chen, the museum’s artistic director, curated the exhibition and invited ten contemporary sculptors to display public artworks of various styles, bringing a symbiotic harmony to the site of Zhongguancun No. 1 technology park; together, they constructed an exquisite future vision of the marriage of art and technology.

Participating Artists

Zheng Lu

Zheng Lu was born in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, in 1978. He graduated from the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts’ Department of Sculpture with a bachelor’s degree in 2003. He then studied at the Beaux-Arts de Paris in 2006, before receiving his master’s degree from the Sculpture Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2007. He currently resides in Beijing.

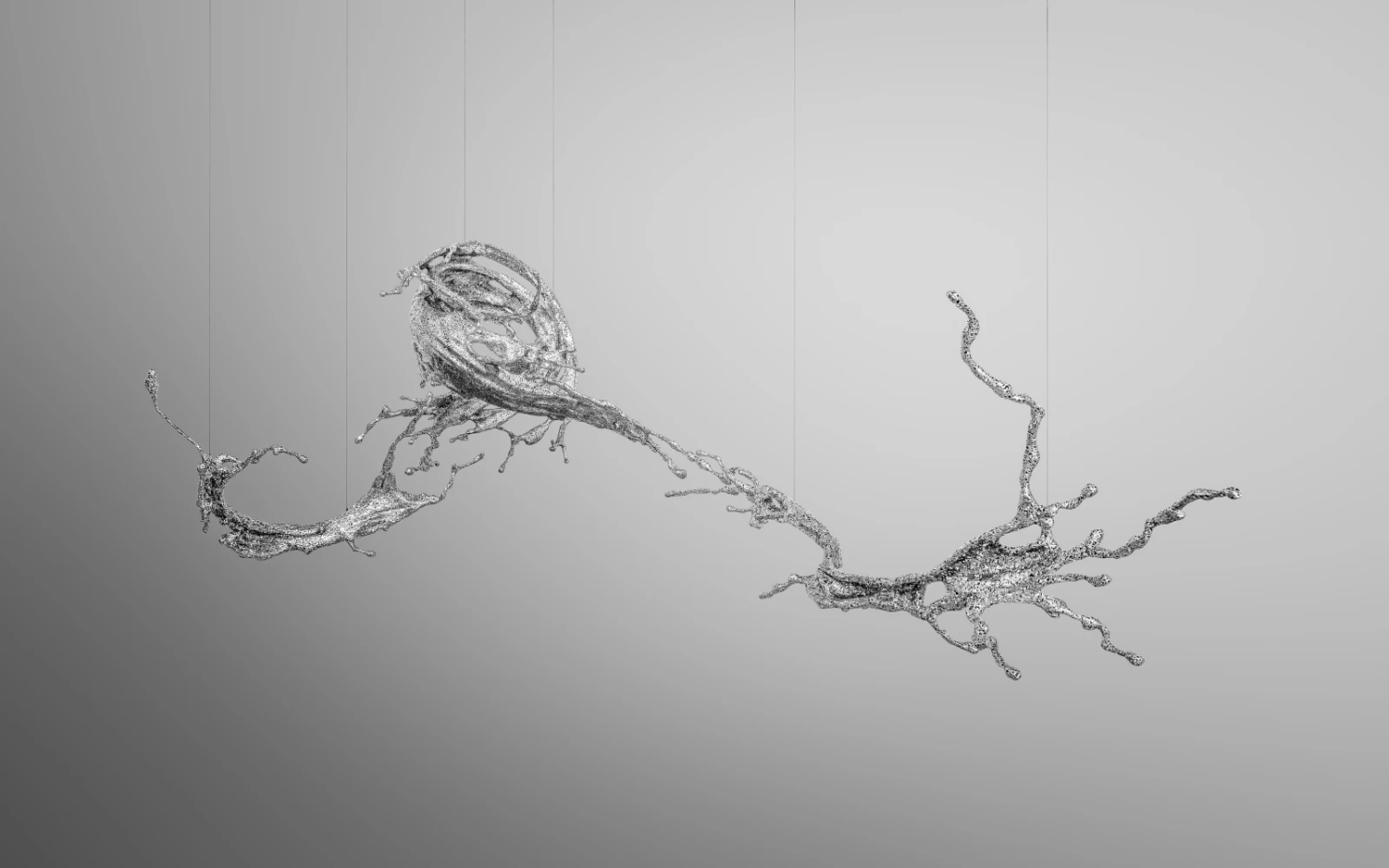

“Rhythmic Vitality”

“Zheng Lu’s unique sculptural technique dispenses with the solidity and heaviness of traditional sculpture, allowing hard metal surfaces to express the surges and elegance of splashing water. Water in Dripping, Zheng’s gravity-defying series of riverine sculptures started in 2008, draws on Tang dynasty poet Bai Juyi’s poem, Playing with Water (‘The animated like flowing waters / the calm like still waters…’) for its inspiration. The artist makes the movement of water described in the poem essential to the sculpture, so that the work perfectly captures the lightness and mutability of water splashing mid-air, giving the viewer a pen-and-ink-like sense of ‘rhythmic vitality’. In conveying his understanding of traditional Chinese poetry through the medium of contemporary art, Zheng’s works open up new possibilities for the interpretation of traditional culture.”

—Cheng Chen, curator

Growing up in a family versed in traditional Chinese literature, Zheng Lu showed a keen interest in calligraphy, and the use of calligraphic elements in his artistic creations imbues his sculptures with a unique aesthetic and meaning. All the characters used in these intricate sculptures derive from Chinese literature and poetry. During the creative process, and despite having been subjected to complex techniques, such as laser cutting, shaping, welding, and polishing, the cold stainless steel nonetheless appears soft and seamless, its lines smooth and delicate, lending the works an aesthetically pleasing balance of graceful fluidity, and of firmness tempered with flexibility.

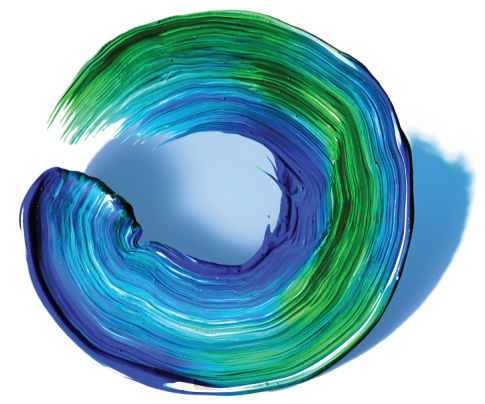

“Water in Dripping: Blue” (淋漓–蓝), 2022. Image courtesy of HOFA Gallery.

The works on display are underpinned by the interaction and conflict between sculpture and text: here, Bai Juyi’s Playing with Water is incorporated into the works as a textual source; while there, the sculptures use the words’ messages as expressive tools through which to transcend the meaning and connotation of the words themselves. Just as Bai Juyi’s poem is ostensibly a description of the states of water – from movement through to stillness – but ultimately refers to human reason, the poem’s meaning springs from the axiom “A man does not seek to see himself in running water, but in still water,” from the classical Chinese philosophical text, the Zhuangzi. The stainless steel of the anti-gravity sculptures recreates a vista of water in motion, thus bringing about the copying, transfer, and restructuring of textual information, while paying homage to the ancient Chinese traditions of “transmission by copying” and “copying models”.

Zheng Lu believes that cities and art are indissociable from one another, and that, as material and cultural life improve, urban art will take on a more diversified appearance. For artists, bringing their works forward for display in the public space is a big step in itself, but being able to make works of art that are accessible to people – touchable, even – is the most meaningful part of all.

Laisser un commentaire